“Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?” — New International Version Bible Matthew 7:3

On a sunny August day, you see your shadow. The shadow you see is a reflection of your physical body and very visible. But not all shadows are so easy to see. There’s another shadow within us that reflects our personality. This shadow can be elusive and hard to recognize.

It is ironic that what annoys us most about someone else is often what we don’t like in ourselves. If we don’t like a trait such as selfishness or tardiness in another person, it is often because we don’t like that aspect of ourselves. Instead of accepting ourselves as flawed human beings with both positive and negative traits, we tend to dismiss or repress what we are ashamed of. We hide these things, letting them become part of our subconscious, or what noted psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung called our “shadow self”. This is the shadow within us.

Most of us aren’t very aware of our shadow self. Its quietly part of our subconscious, until it pops up at the worst possible moments, such as when we’re stressed or tired. Such an unruly shadow can burden us with emotions like anger, guilt, shame or disgust.

“Shadow work” can help us become more aware of our shadow self. Shadow work is challenging! It takes effort and continued practice to develop a conscious relationship with those parts of ourselves we judge as unlovable or unworthy.

Several years ago my husband and I attended the Des Moines Art Festival with a strong “look but no buy” resolve. As we neared the entrance area, we spontaneously decided to stroll through the Art Festival without talking. We’d just be in silent appreciation of our surroundings and simply notice if or when we felt drawn to a piece of art. We agreed to share our observations with each other before leaving the festival. What we did not realize was how dangerous our simple game might be!

Interestingly – of the hundreds, or perhaps thousands of art works – each of us felt drawn to only one piece of art. What floored us was that we were both attracted to the very same piece of art! Now, how could we not be tempted to buy the piece called “Broken Copper”?

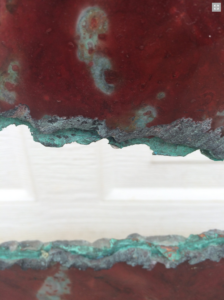

“Broken Copper” was actually rather homely, full of rough edges and flaws. It consisted of a round piece of copper treated with salt, then sandwiched and fused between two larger round panes of clear glass. After fusing, the artist cut out a section of the circle sandwich, leaving rough exposed edges that eventually oxidized to a greenish color. Where salt had been sprinkled on the copper, little bursts of blue contrasted with the deep red color of the copper.

The artist harmoniously displayed the flaws within the copper and glass fusing, causing them to become deeply beautiful and whole.

We yielded to temptation and purchased the piece. “Broken Copper” inhabits our living room and serves as a daily reminder to accept our flawed humanity, and to realize both light and dark are allowed and used by God.

When we work with our shadow self, we address the projections we put on others. We turn those projections inward instead, and gently listen to what they tell us. Only then can we heal those aspects within ourselves. This important work is done by asking questions like these:

- What is making me feel so irritated with this person?

- Where does irritation live within me?

- What frightens me about this person?

- Who or what is it that this person’s behavior(s) remind me of?

Carl Gustav Jung talks of the challenge of shadow work: “There is no coming to consciousness without pain. People will do anything, no matter how absurd, in order to avoid facing their own soul. One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

Although painful, shadow work can help us find a pathway to healing and authentic living. It can help us discover more freedom and a greater capacity to love ourselves and others.

Challenge: To learn more about your shadow, try one or more of the following exercises:

Exercise One: Notice what shocks, infuriates, bothers, disturbs or scares you over the course of one day. Journal about each situation and what important information your emotional reactions might be revealing about your shadow self.

Exercise Two: Pay attention to your dreams, because your subconscious often appears in images and stories as you sleep. Keep a journal by your bed and when you awaken in the morning, write a few notes about your dreams and what they could be telling you about your shadow self.

Exercise Three: For one day, keep a mental log of each time you catch yourself having judgmental thoughts about another person. At the end of the day, review your mental log and consider what your judgmental thoughts can teach you about your shadow self. We usually judge others before we are aware of how we are judging ourselves for the same thing.

Exercise Four: Find some paper and a pen, and try the following exercise, adapted from author Byron Katie’s Judge-Your-Neighbor Worksheet. This exercise uses a simple process of inquiry that can help you own your own judgments and turn your focus to the plank in your own eye:

First, recall a stressful situation with another person that is still fresh in your mind. Return to that time and place in your imagination.

Then write a simple statement about who angered, upset or disappointed you in this situation and why. For example: I am angry with John because he doesn’t listen to me about his health.

Now, with an open heart, ask yourself four questions and write your answers down:

- Is it true? (If no, move to 3) Yes _______ No _________

- Can you absolutely know that it’s true? Yes _______ No__________

- How do you react, and what happens when you believe this thought? For example: When I think John doesn’t listen to me about his health, I feel frustrated and sick to my stomach and give him “the look”

- Who or how would you be, in the same situation, without the thought? For example: I would be less anxious.

To finish the exercise, turn your original simple statement around in three ways along with one specific example of how each “turnaround” is true:

Turnaround #1: Put yourself in the other’s place.

I am angry with myself because I don’t listen to myself about my health.

Example of how this turnaround is true: When John and I were talking about his health, I was out of control emotionally and my heart was wildly beating.

Turnaround #2: Put the other person in your place.

John is angry with me because I don’t listen to him about his health.

Example of how this turnaround is true: I interrupted John and started to raise my voice when he was sharing his concerns about his health.

Turnaround #3: State the exact opposite.

John does listen to me about his health.

Example of how this turnaround is true: John put out the cigarette he was smoking when we started talking. In that moment, he was apparently listening to me about his health (even though he lit another one five minutes later).

“What we cannot admit in ourselves we often find in others. If a person—who speaks of another person whom he hates with a vengeance that seems nearly irrational—can be brought to describe the characteristics which he most dislikes, you will frequently have a picture of his own repressed aspects which are unrecognized by him though obvious to others.” June Singer, Boundaries of the Soul: The Practice of Jung’s Psychology